Jocelyn Akins knows her audience.

“Wanna bust your balls all day in the field with me tomorrow slinging frozen beaver?”

This is the text I receive. Entirely out of the blue. Entirely unsurprising, given who it’s coming from.

Jocelyn Akins (Dr. Akins if we want to get official; Jos, if we want to get real) is a wildlife biologist living and working in the Columbia River Gorge. For more than a decade I’ve followed her career. I have footage of Jocelyn practicing the defense of her dissertation – she now holds a PhD in Conservation Genetics. I’ve watched as she’s raised 2 rascally kids, while also building a non-profit – the Cascades Carnivore Project. Which quickly went from infancy to national headlines in the span of 15 years.

And so, when the message comes in, I’m game. Jocelyn is planning to set up a wolverine monitoring station – basically a motion-triggered wildlife camera aimed at a bit of bait – in the Mt. Adams wilderness. Of course I want to sling frozen beavers, whatever that means. Because how often do you get the chance to learn firsthand what it takes to study rare carnivores in the high Cascades?

The day begins in the dark. A pre-dawn push to get up and get out. When your commute includes 8 miles of post-holing through feet of snow, you can’t risk being caught out late at night. Our first stop is a non-descript building with a padlocked door. The last place you’d expect to find a treasure chest disguised as a chest freezer. The lid squeaks as Jocelyn lifts it and pulls the loot out. Black plastic garbage bags, each containing a single frozen beaver (a donation of animals recently culled). As a mere Homo sapiens, this appears more crime scene than bounty, but to a wolverine, these beavers are pure gold.

Wolverines are solitary creatures, known for their ferocity. Jocelyn will tell you that they have a “circumpolar distribution” in the northern hemisphere. I will tell you that means you can find them all around the world in cold northern places: Scandinavia, Russia, Mongolia, China, and here, in North America. Historically, wolverines could be found as far south as the Sierra Nevada in California and wolverines roamed freely in the North Cascades – but then all that changed.

Throughout the 20th century wolverine numbers began to drop in the Pacific Northwest. Slowly at first, and then precipitously. The decline was not the result of a singular source, but the combination of many; large-scale timber extraction, government programs of predator poisoning aimed at wolves, bears and coyotes, road-building, and to a smaller extent, fur trapping. By the 1920s, wolverines were extirpated from Washington, Oregon, and Northern California.

But these beasts are stubborn. And so is Jocelyn.

In 2005, biologists with Yakama Nation captured a photo with a remote wildlife camera. A single wolverine had returned to Washington. But where did it come from? And might there be more?

These are the questions that drive our early morning road-trip; It drives a lot of the trips and hikes and back-breaking work that Jocelyn and her team must do to try and track a creature known to have travel patterns nearing 800 square miles (a similar-sized home range to that of a grizzly bear). But I am not a scientist. And the chasm between what we are doing today and an answer that may be years, even decades, in the making seems insurmountable.

What I want to know is the plan for the day. Beginning with, how is a sponge, secured in a Ziploc, that is wrapped in a waterproof bag, and then strapped to the roof of the car still pungent enough to be smelled INSIDE the fast-moving vehicle?!

“Oh, that’s the scent lure!” Jocelyn laughs. “Yeah, sometimes our whole house will smell like that, even if I never bring it inside. It just, like permeates your clothes.”

[Wanna see Jocelyn and the scent lure in action? Check her out in this quick 40 sec video. Wish we had a scratch-and-sniff option so you could experience firsthand!]

“It’s surprisingly, shockingly stinky” Jocelyn tells me. This, of course, does not need to be said. When I ask what could possibly make something so smelly Jocelyn catches me by surprise – she pulls out a piece of paper and begins to read…

“Skunk essence, beaver castor, marten lure, anise oil…oh wait, that was the recipe for lynx lure!”

Jocelyn laughs and then skips ahead to the next recipe, this one for Wolverines. She proceeds through a list of ingredients that sounds more Hogwarts than high-science and I can’t help but wonder is this really how it’s done? Isn’t science about data and protocols, methods and microscopes? I wonder if my being there has thrown off the plan, corrupted the system. Will I need to be accounted for somewhere in her facts and figures (“1 scent lure, 1 frozen beaver, 1 non-scientist with obnoxious questions”). But I can’t help but wonder. Jocelyn is trying to find the proverbial needle in a haystack, but the hay is covered in feet of snow and the needle likes to move. How can this even be possible?! In front of us is the equivalent of 40,000 football fields. This is the territory that Jocelyn is tasked with placing a single detection station in hopes of capturing a creature that may, or may not, be there – and all we are armed with is a stinky sponge, a frozen beaver, and a camera.

I look out on acres upon acres of land and immediately feel overwhelmed by what Jocelyn has to do. Isn’t there a better way? Like helicopters? Or heat-seeking gadgets? Some way to speed up this monumental task? Of, course money and logistics aside, for this type of science – there is no quick and easy way. Jocelyn and her research team know the terrain. They pore over maps, they get out and hike. They understand which creek follows which watershed and how two landscapes might connect. They are doing the science to begin to understand how a nomadic and wild creature might move through this place. Still for all the knowledge she has gained, the data she has collected, today Jocelyn must focus on a single step – and so as fat and icy raindrops plop down on our jackets I ask – what are you trying to figure out right now?

Jocelyn, map in hand, looks out over a subalpine lake and then back at me. She flashes me her smile – and I can tell there is some amusement at my simple question, partly because she knows this is what to expect when she invites me along, partly because its simplicity masks the complexity of what she must do. And so she begins with the science, of course.

“This is actually the start of a saddle, so we could place it right on top and get scent dispersion on either side, or there’s some nice meadow complexes over there where their prey might live, and we could get good flow down to the east…”

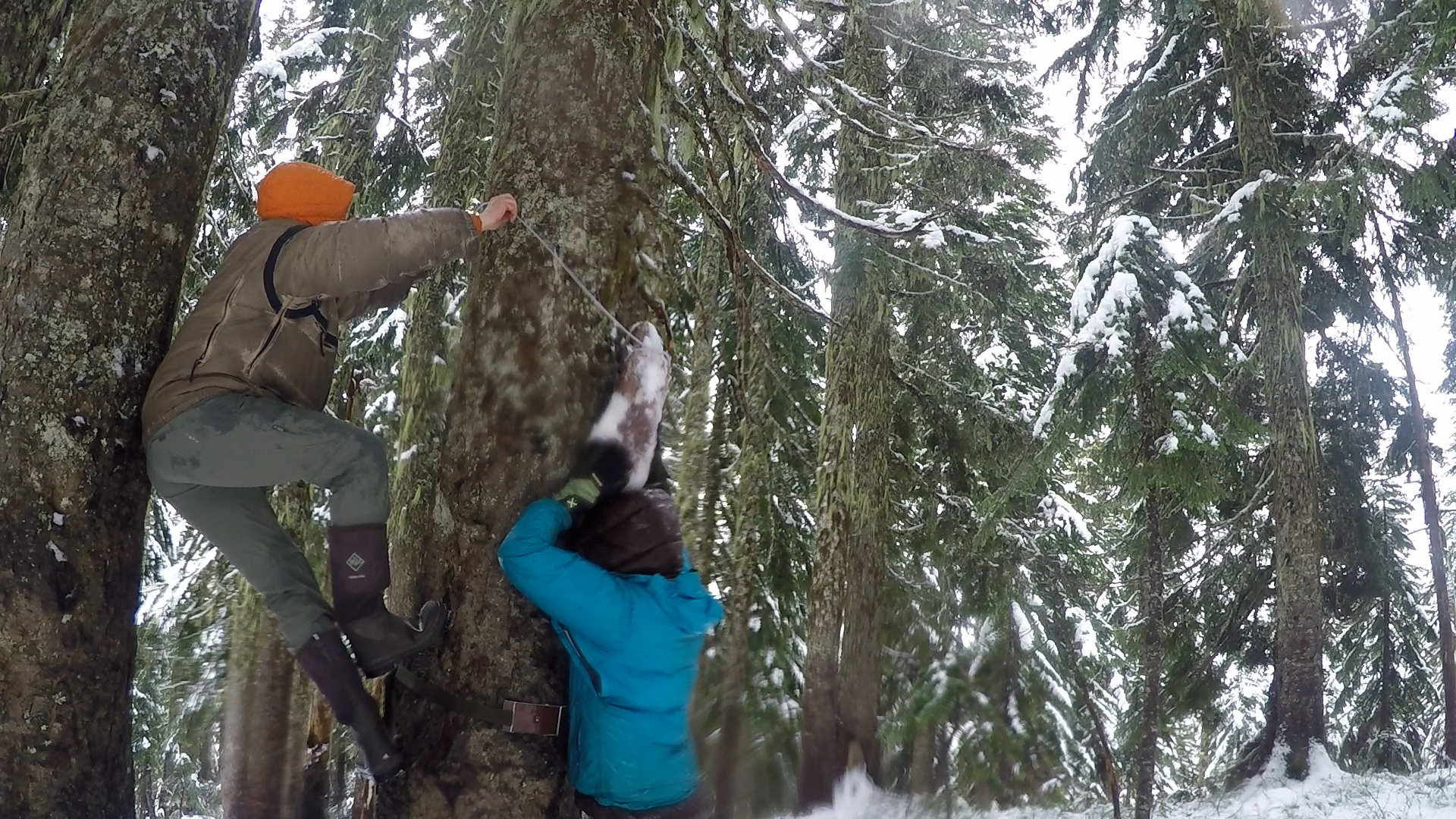

We eventually land on a spot, at the base of a talus slope. A smaller saddle with air moving down a drainage across a likely route for a wolverine. The frozen beaver is hoisted into a tree and held aloft on my head, while Jocelyn balances on tree pegs and pulls the cable taut to lash the bait to the tree.

The scent sponge, delicately removed from its first bag, and then second, is hung nearby. All are placed with future snow in mind. This is the early season after all. Jos tells me that future visits to check the camera and re-bait, won’t be such an easy hike.

With bait and scent lure placed, Jocelyn heads to another tree and hangs a motion-triggered camera. Batteries? Check. Fresh SD card? Check. Trigger working? Check.

“I have so many photos of me jumping in front of the cameras to make sure they’re working.”

Six months later she’ll be back. She’ll end up setting 5 more cameras as part of collaborative project to study wolverines across the American west. Jocelyn and her team will add 20 more stations all placed in suitable wolverine habitat, from Interstate 90 down to the Columbia River. Part of a project to monitor the impact of climate change on wolverine populations.

And then, in 2018, one of these cameras will capture something special. Something not seen in the south Cascades in nearly a century. A mother wolverine and her kits.

The image will make headlines of its own. It documents the potential return of, not just passing through, of a creature that once called this place home. Reporters will join Dr. Akins on subsequent slogs to cameras and to a den. And then eventually, they, we, will leave and Jos will carry on. Not so unlike the wolverines she’s studying. Most comfortable in the rugged terrain of the high alpine, stubbornly seeking something that unites us all.

Related links: